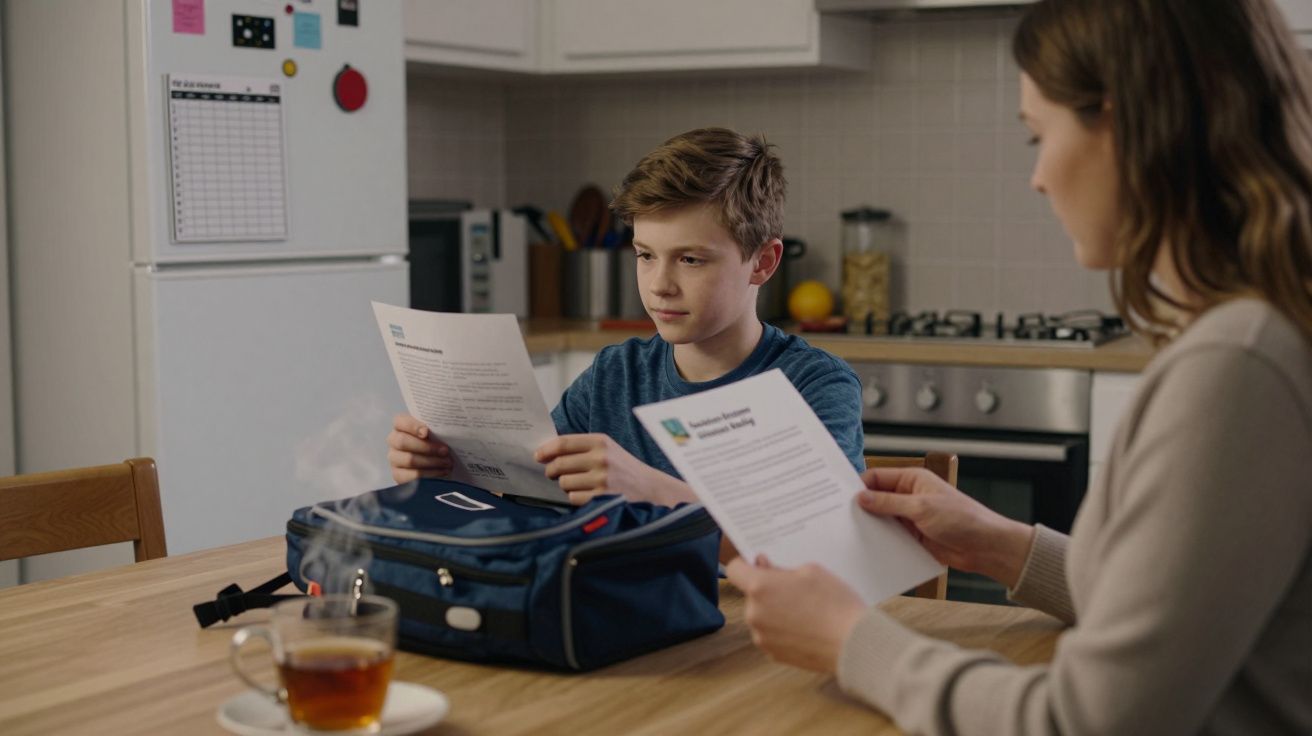

At a kitchen table in Derbyshire, the hum of the dishwasher is louder than the usual arguments about worksheets. A Year 8 boy is packing his bag for the morning, glancing at a timetable stuck to the fridge. No maths questions tonight. No history project to cobble together with glue and late-night panic. Just 20 minutes of reading and one short quiz he already finished in form time.

His mum checks the crumpled letter again, the one sent home by school at the start of term. “We are trialling a reduced-homework policy,” it says, “to prioritise focused practice in lessons, reading at home and pupil wellbeing.” No fanfare, no headlines, just a quiet shift in how evenings are meant to feel. She’s not sure whether to be relieved or suspicious.

Across a few counties in England and Wales, similar letters have landed with the same soft thud. Multi-academy trusts have sliced homework hours by half in Key Stage 3. Some primary schools have dropped formal worksheets entirely, keeping only reading logs and occasional spellings. In governors’ minutes, it’s called “rationalisation”. In living rooms, it feels like a small revolution.

The obvious question hangs in the air: if homework shrinks, do exam results fall? Early figures suggest the answer is more complicated - and more interesting - than many expected.

Why some schools are quietly cutting back

For years, homework has behaved like weather: everyone complains about it, few people think they can change it. Research, though, has been nudging at the edges of that assumption. Large reviews find that traditional homework has little measurable impact in primary, and only a moderate impact in secondary - and that impact depends heavily on quality, not quantity.

Heads in several counties have been circling the same three pressures:

- rising anxiety and burnout in pupils, especially post‑pandemic

- exhausted teachers spending hours setting and marking low-impact tasks

- widening gaps between pupils with quiet desks and Wi‑Fi, and those sharing a sofa and a single phone.

One secondary head in Staffordshire puts it bluntly: “We realised we were sending stress home, not learning.” Parents were emailing about bedtime battles; staff were chasing missing work from pupils with no printer and no space. The question shifted from “How much homework is enough?” to “Which parts of this are actually worth the fight?”

There’s also a curriculum reality. Newer exam specifications lean heavily on deep understanding and spaced recall, not last-minute cramming. That can be built into lessons as much as it can be sent home. Homework is being treated less as a rite of passage and more as a tool - one that can be sharpened or put down.

What the ‘less homework’ model actually looks like

This isn’t a free‑for‑all or a ban. The schools trimming homework are mostly doing three things, quietly and consistently.

First, they’re capping time. In one Midlands trust, Year 7–9 pupils are told to expect no more than 30–40 minutes a night on average, including reading. Sixth formers still get substantial independent work; exam classes see a gradual ramp‑up, not a cliff edge.

Second, they’re narrowing the focus. Out go elaborate poster projects and open‑ended “research” that end with parents on Google at 10 p.m. In stay:

- short retrieval quizzes

- vocabulary and formula practice

- reading for pleasure or background knowledge.

Teachers build more rehearsal into the school day: starters, low‑stakes tests, paired explanations. The homework then acts as a light extension, not a desperate plug for holes.

Third, they’re tightening feedback loops. Homework that is set is either self‑marked in class, auto‑marked online, or used to inform the next lesson. If a piece won’t be looked at for a fortnight, it’s likely to be cut. Let’s be honest: nobody stays motivated by a worksheet that disappears into a marking pile for weeks.

We’ve all seen the other version - glossy homework menus, stickers, elaborate tracking sheets that collapse under their own admin. The quieter model looks boring on paper. That’s partly the point.

“Home isn’t a second classroom, it’s the rest of the day,” says a deputy head in North Yorkshire. “We want home tasks that fit into real lives.”

What early data shows for tests and exams

In schools that have trimmed homework for at least two years, three patterns are emerging from internal tracking and local authority data.

1. Exam results are holding steady - and sometimes nudging up in specific groups.

In two English counties where clusters of schools reduced homework in Key Stage 3, average GCSE results in English and maths have stayed broadly in line with similar schools that kept traditional policies. In one trust of 11 secondary schools, disadvantaged pupils saw a small but noticeable rise in science grades after the change, while peers stayed flat. Heads there link it to more consistent in‑class practice and fewer incomplete homework tasks dragging down confidence.

2. Engagement is improving more than raw scores.

Pupil surveys in several pilot schools show:

- fewer late‑night homework “panics” reported by families

- higher rates of homework completion on the smaller set tasks

- a drop in behaviour incidents in the last lesson of the day, which leaders attribute to reduced end‑of‑day fatigue.

Attendance, particularly on Fridays and around mock‑exam weeks, has ticked up a fraction in some settings. Hard to prove causation, but staff talk about “a calmer feel” when pupils aren’t carrying three overdue assignments in their heads.

3. The quality of work has sharpened.

When teachers aren’t spreading themselves across twenty different task types, they can design and refine a handful that genuinely prepare pupils for exams: past‑paper questions, targeted reading, vocabulary drills. Internal assessments show fewer “didn’t attempt” answers, especially in extended writing, where pupils say they feel less overwhelmed and more practised.

None of this means homework doesn’t matter. It suggests that trimming the flab, rather than piling on hours, may give you the same – or slightly better – academic outcomes, with less collateral damage at home. Cutting homework hours hasn’t cut grades – so far. The caveat is important: these are early signals, not ten‑year studies.

How it changes life at home

For families, the shift lands not as a policy but as an evening that feels different. There is more unscheduled time - but also more ambiguity. If school isn’t dictating every half‑hour, what should happen after 4 p.m.?

Some parents worry that less homework means lower ambition. Others quietly welcome a break from nightly stand‑offs over fronted adverbials. Most are somewhere in between, trying to work out how to support learning without recreating school at the dining table.

A few small habits seem to help:

- Keep one anchor, not a full timetable. Decide on a simple default: “After tea, 20 minutes reading or revision, then screens.” Consistency matters more than complexity.

- Ask about today, not just tomorrow. Swap “Have you got homework?” for “What did you find hard today?” Often the best support is a five‑minute chat or a quick look at class notes.

- Protect genuine rest. Reduced homework isn’t an invitation for more tutoring, more clubs, more busyness. One or two evenings that are properly free can leave pupils fresher for the learning that does count.

We’ve all had that moment when a child’s schoolbag feels like a second job. A lighter homework load can remove weight, but it also asks families to decide how to use the space. That’s both the risk and the opportunity.

The new homework landscape, in brief

| Change in approach | What it looks like | Why schools are doing it |

|---|---|---|

| Less volume, tighter caps | 20–40 minutes most nights in lower years | To cut busywork and protect wellbeing |

| Simpler, exam‑linked tasks | Retrieval quizzes, reading, past‑paper style questions | To focus on what actually moves grades |

| More learning in lessons | Extra practice and feedback built into class | To reduce gaps created by home circumstances |

The quiet shift in some counties is not about throwing homework out; it’s about admitting that more is not always better, and that evenings are part of the learning ecosystem, not just extra curriculum time. As more cohorts move through this leaner model, the data will get clearer. For now, the signal is tentative but consistent: when schools do less, on purpose, pupils do not necessarily achieve less.

The bigger question may end up being less “How many minutes?” and more “What sort of lives do we want schoolchildren to have outside the classroom - and how much are we willing to trust that some of that life will teach them things no worksheet ever could?”

FAQ:

- Does less homework mean my child will fall behind? Early evidence from pilot schools suggests that when homework is better designed, not just shorter, exam results stay broadly stable. The key is what schools put into lessons and the quality of the tasks that remain.

- Should I top up with extra work at home? If your child is coping well and progressing, you probably do not need to. Occasional targeted practice or reading is useful; constant extra worksheets can backfire by increasing stress.

- What if my child is a high achiever who likes lots of work? Encourage depth rather than volume: enrichment reading, challenging problems, wider projects driven by their interests. Talk to teachers about extension ideas rather than recreating formal homework.

- How can I tell if a reduced-homework policy is working in our school? Look at more than grades: ask about homework completion rates, pupil surveys, and how teachers are using lesson time. Governors’ reports and parents’ evenings are good places to raise these questions.

- Is this trend likely to spread to all schools? Not quickly. Homework policies are set locally, and many schools will wait for clearer long‑term data. But the fact that some are experimenting - and not seeing results collapse - means the debate is unlikely to disappear.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment